QUINTON, Okla.— “He’s still not talking yet,” said Autumn Sisco, staring down at the beefy little boy in the Buzz Lightyear sweatshirt playing at her feet. She scooped him up and swiped at his runny nose with her shirt sleeve.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with him,” she said, sinking back into her living room sofa, watching the two-year-old bounce like a pinball across the living room floor to the kitchen, down a hallway and back.

This isn’t what her life is supposed to look like. She’d imagined herself a college co-ed, partying somewhere with a drink in her hand, giggling with girlfriends, or pulling an all-nighter for an exam she didn’t study for.

Instead she’s an underemployed 19-year-old mother and wife, struggling to keep her young marriage together and raise a kid in a small rural town where opportunities are few and disappointments are many.

“Trouble,” she lamented quietly. “You’re always in trouble here. There’s nothing positive.”

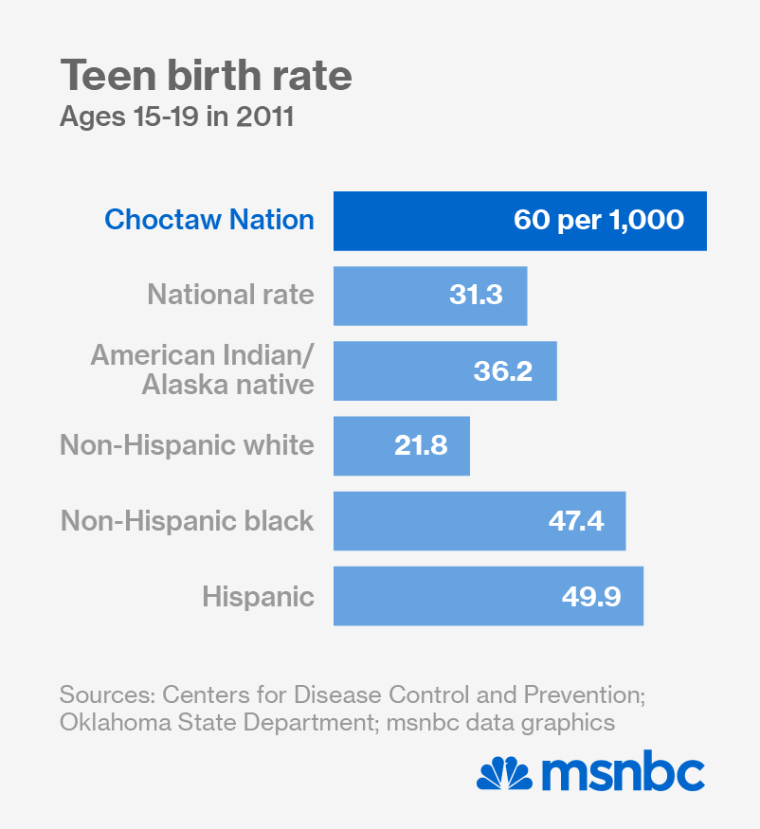

Life as a teen mom could be difficult under any circumstances. But it’s even more so here in the Choctaw Nation, a vast, rural expanse in southeastern Oklahoma where poverty and unemployment are rampant and the teen pregnancy rate is nearly double the national average.

While the teen birth rate has fallen drastically among all racial groups over the last two decades, the pregnancy rate for American Indian teens between 15 and 19 years old is 36.2 per 1,000, 15 points higher than their white counterparts and about 5 points higher than the national average, according to the Center for Disease Control. American Indian teens also lead all other groups in the rate of repeat births.

With so many young parents in the Choctaw Nation— an area larger than the state of Massachusetts— tribal leaders have made outreach to teen parents a priority. Those efforts were given a boost recently when the Obama administration designated the Choctaw Nation one of its first five Promise Zones, a program aimed at strengthening the relationship between impoverished communities and the federal government.

The tribe hopes to use the designation to access grants they’ll use to bolster some of the work they’ve already been doing, particularly around youth and families.

“What we’re doing isn’t just about changing today’s parents,” said Angela Dancer, senior director of the Better Beginnings Program, which serves at-risk and high-needs families. “It’s about changing the parents of the future.”

Dancer’s program helps ease the burdens many of these families face, including food insecurity and access to adequate medical care. The outreach workers, all of whom are Choctaw, do at-home visits and try to walk young mothers through the uncertainty of new parenthood.

They give away free diapers and car seats. And they help overwhelmed teen parents deal with stress management, create a healthy environment and teach them skills to build stronger attachments to their babies, all of which are challenges in the small impoverished communities that dot the Nation.

“They’ve had people come in and out of their lives and tell them all of the negative things about their weaknesses. But we help them understand their strengths,” Dancer said. “If we didn’t go out and touch them where they are, there’s no way we could touch as many as we do.”

But the challenges of reaching this demographic, many of whom are high-school dropouts without much financial or emotional support from their families, can often seem unsurmountable.

They’re geographically spread across very isolated communities within the nearly 11 counties that comprise the Nation’s service area. And emotionally, many are saddled with feelings of shame, guilt and the generational curse of teen pregnancy. Others are victims of domestic abuse.

“So many of them just close themselves off because they’re already worried about being judged -- judged for getting pregnant in the first place,” said Hanna Wood, 29, an outreach worker who has worked with Sisco and her family.

The Nation also offers sex-education courses to schools within the Nation’s boundary, an effort that remains somewhat controversial in an area of the state dominated by conservative politics and where abstinence-only education is the preferred model. Outreach workers have found navigating the politics of teaching teens and pre-teens about safe sex and personal boundaries a delicate endeavor.

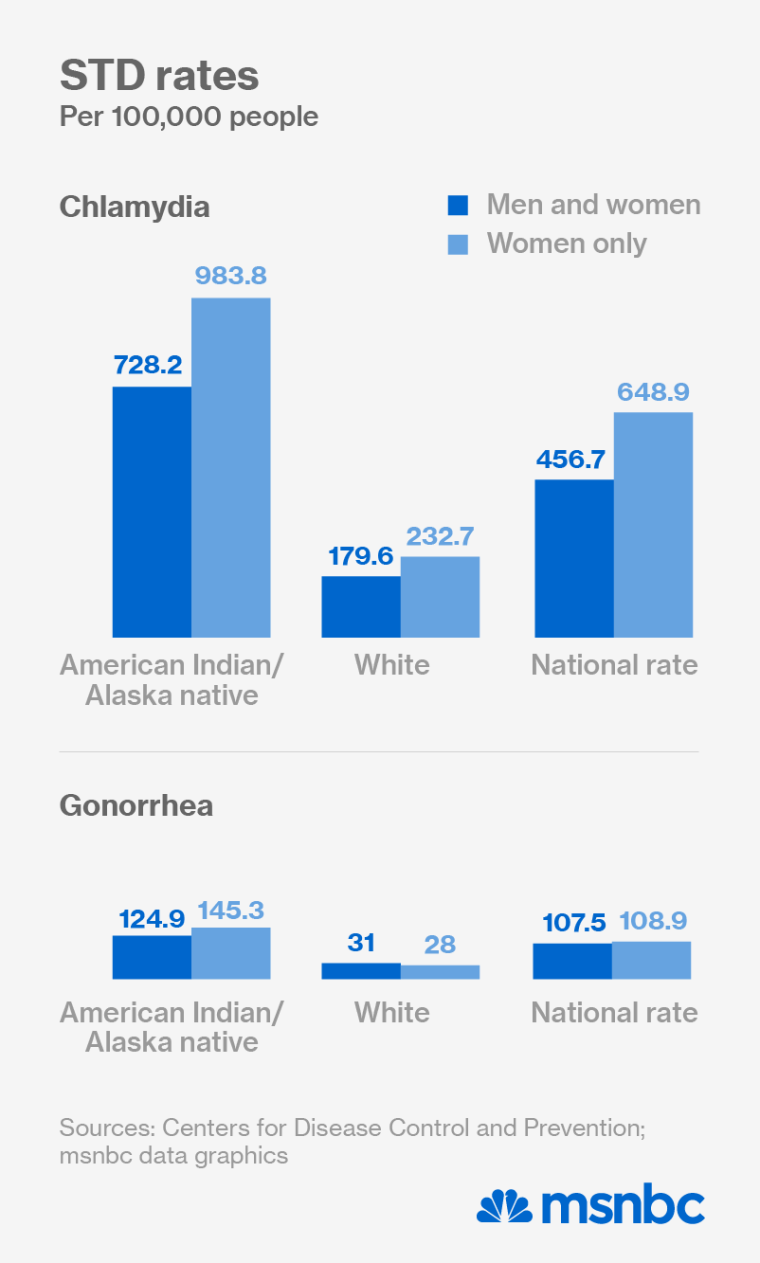

Nearly all Choctaw Indian students attend public schools where the majority of students are non-Native. And despite high rates of teen-pregnancy and a rate of sexually transmitted disease that is four times the national average, many public school districts within the Nation won’t allow the sex-ed courses taught in their schools.

For More on the Choctaw Nation see our photo essay: Hope on the Horizon for Choctaw Nation

Some schools will allow parts of the curriculum to be taught in their classrooms but won’t allow others, like condom demonstrations. On a recent evening nearly two dozen eighth graders whose school forbade such a demonstration gathered at Choctaw Nation outreach services headquarters, giggling and guffawing as an instructor urged them to slide a latex condom down their fore and middle fingers.

“We’re dealing with some pushback,” said Dancer. “But the statistics don’t lie.”

National politics have also become intertwined with the Nation’s efforts, as much of the funding for Better Beginnings is tied to the hotly-contested Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare. Last year, sequestration cuts and a shrinking number of grants, stripped funding from many of the tribe’s critical, government-funded programs. Better Beginnings was no different.

“I don’t care about the politics of it. I’m not a political person,” Dancer said. “But that’s what my funds are tied to. If that means it gets reinstated over and over, that’s just fine by me. “

While programs to help at-risk youth in the Nation have grown from just a few 20 years ago to dozens today, there still are major gaps. The nearest substance abuse treatment facility for juveniles is nearly 300 miles away, and there’s no in-patient mental health facility or homeless shelter. And there’s still a stigma around many of the issues these young people face, a hurdle outreach workers must handle with care.

“It’s the cycle. Their mothers went through the same thing,” said Shonda Shomo, an outreach worker with the Better Beginning program. “I was a teen mom. I was 18, so I know what they’re going through. I just keep encouraging them. And that’s something they don’t always hear from their mother figures.”

On a recent afternoon, Hannah Wood, another outreach worker, visited Sisco at her apartment, which she shares with her 17-year-old husband Mike and their son, Bobby. Wood joined Bobby on the floor with a worksheet of benchmarks that a child Bobby’s age should be hitting and a stacking game with various sized bowls. A big part of Better Beginnings and its sister program, Support for Pregnant and Parenting Teens, is identifying developmental delays in children, a problem that is often overlooked in poor communities where access to quality healthcare is limited.

Sisco sat back on the sofa, swallowed up by an oversized hooded sweatshirt, watching Bobby shakily slide the smaller bowls into the bigger bowls.

Over the years, Sisco said she’d grown accustomed to having Wood around, especially during tough times, of which she said there’ve been many.

“She helped me learn how to take care of my child and helped me with my anger,” Sisco said of Wood, who until getting married recently had been a single mother of a little boy not much older than Bobby. “She taught me ways to keep it from harming Bobby, to take him away before I get to a bad place.”

But after months of progress, things have slowly unfurled.

Sisco said Bobby almost died a few weeks ago after getting into a bottle of his grandmother’s muscle relaxers. They were able to get him to the hospital on time to have his stomach pumped. And after about seven hours at the hospital, Bobby finally woke up.

Sisco said she has also seen her own life flash before her eyes. A year or two ago, Sisco said, she was hanging out with friends when she was passed a blunt— an emptied cigar filled with marijuana. But after toking from it, she said she began to feel sick and eventually passed out. She thinks the blunt was laced with something.

“I OD’d,” she said. “I saw a big white light and heard a voice saying that I didn’t make it to judgment and that I was going to hell.”

She didn’t die, but she landed back in Quinton -- a small town which she described as hellish in its own right.

Autumn and Mike got married about six months ago on the Quinton High School football field before a game. The couple soon moved in together with their little boy in tow. Mike, a senior in high school, has been consumed with football and wrestling practice after school for the better part of a year. His extra-curriculars have left Autumn, a Certified Nursing Assistant, to bear the brunt of the family’s financial responsibilities. Fights over “dumb stuff” have increased and the pangs of new marriage and keeping watch over a rambunctious little boy have become overwhelming.

Things got so bad last year that Autum handed over custody of Bobby to her mother for several months so that she could attend school.

“I didn’t visit much,” she admitted. “I’m still struggling with the idea of being a parent.”

Autumn grew up not too far from the little corner apartment in Quinton where she lives now. When she was a younger teen, she and her friends would spend their days skipping school and breaking into abandoned houses to drink and smoked weed. Her acting out began even earlier, sometime around 6 or 7 when her parents divorced.

Autumn started running away from home. By 13 she was smoking. By 15 she said depression set in and she started sleeping around. She got pregnant when she was a 16-year-old junior in high school. Mike, Bobby’s father, was 15 and a grade level below her.

When word of her pregnancy began to spread, her classmates taunted her and jeered.

“They called me a whore,” Sisco said. When she turned to school counselors “they said I wasn’t going to be anything in life.”

She said that she was literally on her way to get an abortion when her mother convinced her to hold off at least a few weeks until her first pre-natal screening with a doctor.

“I was scared to death,” Sisco said. “The whole time up to that point I was drinking and smoking.”

At the appointment, she heard Bobby’s heartbeat for the very first time. And it changed everything. She was set on having her baby. She returned to school, her belly now bulging, to face down the insults and bullying.

Eventually, Sisco said that school administrators tried to get her removed from school and placed in some sort of alternative academic program. She’d become a distraction and a bad influence on other students, they said.

At the same time, her relationship with Mike was falling apart.

“He ran away from it,” Sisco said. He spent more time with his friends than with her and her growing belly.

“I cried a lot,” she said. “I kept thinking he wasn’t ready and maybe he was going to leave me.”

*****

Mike’s father, who is Cherokee and Choctaw and became a parent himself at 15, sat Mike down at age 10 and made him promise that he wouldn’t make his father’s mistakes.

“One thing he always told me was not to follow in his footsteps,” Mike said after school and wrestling practice on a recent afternoon.

Just five years later, there Mike was, a self-described high school “troublemaker” and knucklehead with a pregnant girlfriend.

“I’m dead,” Mike recalled thinking at the time. He was afraid of having to grow up quickly, of raising a kid while he was still very much a kid, albeit a big one at well over 6-feet-tall and weighing more than 200 pounds.

He wanted to hide, to get away from it all, to shirk whatever responsibility being a father would mean.

What changed?

“Him,” he said, pointing to Bobby, still pinballing across the family’s knotty brown carpet. “And an old principal had a talk with me. He told me if I didn’t change my ways, I’d be in jail. He asked if I wanted some other guy being called daddy by my son.”

“I just had to grow up instantly,” he said, his grey sweatshirt still drenched in sweat from practice.

Autumn’s gaze slid slowly between the little boy on the floor and the big boy leaning with his back against the living room wall, as the big boy talked about wanting to go off to college and then become a football coach someday.

“I can see me having a coaching job. Make it to where Autumn can stay home and clean if she wants or go get a job,” Mike said, smiling wryly over at his young wife.

“I’ll probably never stop working,” Autumn replied, without blinking. “I’m used to being the one that puts food on the table and paying the bills.”

Whatever happens, Autumn said she can’t help but fear things won’t work out. So often throughout her life, good things have been fleeting while the bad tends to linger.

“I’m nervous about the future,” she said. “And my son’s future here.”

Autumn counted nearly a half-dozen drug dealers who sell out of nearby apartment buildings, a far greater number than the good employers in the area.

“My son can’t grow up here,” she said after a long pause. “I don’t want Bobby being 10 years old and somebody offering him drugs. If he is anything like I was he’d be dumb enough to do it.”

Autumn doubts she’ll ever go to college.

“It’s never going to happen,” she said. “No money or time.”

Young people from towns across the Choctaw Nation see few of their friends go off to college. Instead, many hang around town or go to “T.U.” --Tyson’s University, which is a euphemism for the Tyson’s chicken processing plant in McCurtain County.

“Everybody talks about leaving this place, but hardly anyone does,” said Mike. “Most of them are stuck here depending on people. But I just want to ride out of this town to a future.”

But Mike recently put his future prospects in jeopardy. He said he’d been offered a scholarship to play football at a local college, but after he was ejected for fighting during a football game this past season (his second ejection of the season), the coaches threatened to pull his scholarship.

“They said they don’t want any violence at their school,” Mike said, fearing that if he doesn’t get the scholarship he’ll be stuck in Quinton.

For more than two hours Hannah Wood, the outreach worker, sat back and listed to Mike and Autumn recount their lives leading up to that afternoon on the couch. After more than two years of weekly visits and growing closer to the family, so much of the pain the two had shared was news to her.

Driving away from Quinton, Wood seemed deflated or at the very least least at a loss.

“It’s not the good that weighs on you,” she said. “It’s the bad.”

Editor’s note: this is the second of two stories on the Choctaw Nation, exploring the tribe’s outreach efforts to young Indians struggling with poverty and teen pregnancy. The Choctaw Nation was recently selected by the Obama administration as one of five Promise Zones, a federal initiative aimed at helping impoverished communities across the country.

This story has been updated to reflect the reason why Autumn temporarily relinquished custody of her son.