New York Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo, whose chokehold killed Eric Garner on Staten Island in July, has been sued by residents claiming various abuses in at least three separate cases.

In one of those cases, Pantaleo is accused of falsely arresting and humiliating two men, who say Pantaleo searched them illegally, forced them to pull their pants and underwear down in public, squat and cough.

The City of New York settled that claim for $30,000 -- $15,000 for each party involved.

A grand jury earlier this week announced that it would not be indicting Pantaleo in Garner’s death, despite the outcry from community groups who say the NYPD has systematically targeted black and Hispanic men for harassment.

"Claims against members of New York’s finest have swelled by 31% over the past five years. In that time, the city has paid out nearly a half-billion dollars."'

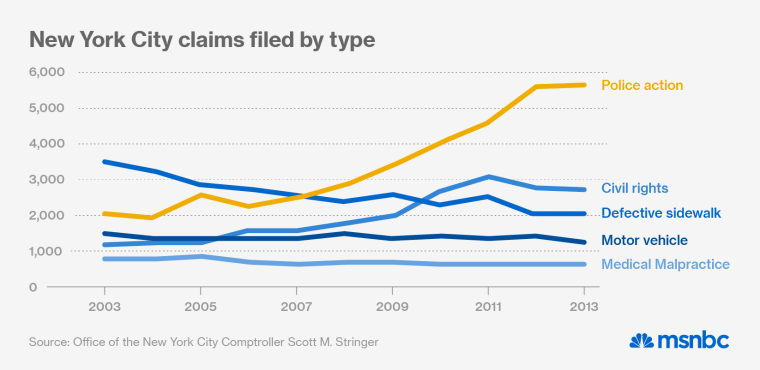

The payout amount in the earlier Pantaleo case is hardly unusual for New York City, where claims against members of New York’s finest have swelled by 31% over the past five years. In that time, the city has paid out nearly a half-billion dollars in claims. According to the New York City Comptroller’s Office, there were 9,500 claims filed against the police department in 2013, to the tune of $137 million. The total amount paid out in fiscal year 2014 has ballooned to $212 million.

Claims against the police department accounted for 37% of the claims against the city by residents, the largest of any of the city’s major agencies, including health and human services, sanitation, transportation, and parks and recreation.

City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer said the mass of claims against the police department are driven by allegations of some sort of violence or abuse. And that the trove of data his office has collected may offer opportunities to minimize those often violent encounters.

Stringer’s office in recent months launched what they call ClaimStat, similar to the police department’s CompStat program for tracking crime. But instead of gathering data about specific crimes and where they occur, ClaimStat identifies where the most claims against police originate. Stringer said he hopes the program will serve as “an early warning system” to help cut back on police behavior that leads to exorbitant claims and back end costs.

"We don’t have to accept that violent confrontations between police and the community are an inevitable part of policing."'

“We do not need to accept the premise that claims and settlements have to go up year after year,” Stringer told msnbc. “We don’t have to accept that violent confrontations between police and the community are an inevitable part of policing.”

Stringer, who took office in January, said that he’s been working with police department leaders and highlighting how focusing on the issue of claims makes good fiscal and moral sense.

“If you see claims, and we’ve seen this, coming from a certain precinct let’s go out there and see what’s going on,” he said. “Let’s find out about the police officers or specific policing policy or make changes. We want this to be an early warning system.”

Under controversial current and former NYPD policies, the costs of claims has skyrocketed. "Stop-and-frisk," a hallmark of the Bloomberg administration, focused police manpower at randomly stopping mostly black and brown young men. A federal judge later deemed that practice violated the constitutional rights of those it targeted and ordered major changes to the policy. Mayor Bill de Blasio campaigned and won office largely on his rebuke of stop-and-frisk. But de Blasio has championed another controversial policy, "broken windows," which calls for police to aggressively attack low-level and misdemeanor offenses.

When elected, de Blasio tapped as police commissioner Bill Bratton, who in the early 1990s served as commissioner under Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Bratton was also an architect of broken windows policing.

Many critics, advocates and supporters of Eric Garner say his life was taken as a result of broken windows policing.

In mid-July, Garner was accosted by Pantaleo and a group of officers on a Staten Island street under suspicion of selling loose, untaxed cigarettes. In a cell phone video that captured the episode, Garner is seen passively resisting arrest before Pantaleo grabs him in a chokehold from behind and wrestles the man to the ground. The footage, shared widely after the incident, shows Garner pleading “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

Moments later, Garner’s body goes limp. He later died on the way to a hospital. The city’s medical examiner declared his death a homicide and that the cause of death was “compression of the neck,” as well as other health factors.

A 23-person Richmond County Grand Jury later declined to indict Pantaleo in Garner’s death.

Garner’s family has filed a $75 million claim against the city. And the comptroller’s office has the exclusive right to try to settle that claim and others before the suit can proceed.

The Garner case offers a good example of police behavior that often leads to costly lawsuits against police.

Because the Garner claim is before his office, Stringer said he could not speak specifically to the case. But he said more broadly he’d like “to head off these violent encounters that result in claims.”

“You do that by knowing where to look and where there are trends,” he said.

The number of claims filed against officers in the city’s precincts vary widely, but are primarily filed from residents in the city’s largely black and Hispanic neighborhoods, Stringer said.

"Even while adjusting for crime rates, the disparities in claims by precinct are stark."'

Even while adjusting for crime rates, the disparities in claims by precinct are stark. Precincts in the South Bronx and central Brooklyn are among the leaders in claims filed against its officers. But there are other wrinkles that the comptroller’s office sees as indicative of other factor perhaps specific to those stationhouses or officers.

Take the 18th Precinct in Manhattan and the 44th Precinct in the Bronx. They had roughly the same number of complaints last year. There were 2,271 in the 18th and 2,191 in the 44th, according to the comptroller’s office. But here’s where the similarities in this context end. For every 100 crime complaints there were 13 claims filed against officers from the 44th while only 2 claims per 100 complaints were filed against cops in the 18th.

“The beauty of this is understanding the claims,” Stringer said. “If it’s the same claim over and over again and it’s the same claim from the same precinct, we can pinpoint it and that is where we can dial up [police commanders] and say, don’t keep this stuff in silos … there’s an opportunity through there for training and reforms.”