Twenty years have passed since Sept. 11, 2001, a day that upended American life as we knew it and started us on a series of ever-newer “normals.” After the Sept. 11 attacks, Americans accepted a marked increase in government control, including the Patriot Act, which allowed for an expansion of government surveillance powers.

Despite what some privacy alarmists might say, we did not lose all our privacy rights after 9/11.

In 2021, on the heels of America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, amid a growing trend of climate disasters and as our nation still battles a raging pandemic, we find ourselves in yet another state of emergency. We do not live in an Orwellian dystopia yet. But this time, we cannot give up our hard-earned rights for what may be a never-ending series of emergencies.

We accepted many mundane privacy violations, including airport screenings by the newly created Transportation Security Administration. But we also accepted more worrisome, larger-scale, longer-term privacy invasions, including the National Security Agency’s bulk collection of data from telephone records. In the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, we even seemingly accepted discrimination against our fellow Americans, including Muslim Americans and other Black and brown Americans who became collateral damage in an unending war on a faceless enemy.

Despite what some privacy alarmists might say, we did not lose all our privacy rights after 9/11. We did, however, accept government privacy invasions in the name of national security and public safety. But that doesn’t answer why we also have seemingly accepted a sharp increase in corporate surveillance and the increasingly harmful data ecosystem that has developed through the advent of the internet and connected technologies.

The rise of the internet, mobile devices and connected technologies has created a data ecosystem where we willingly give up our private information to countless faceless companies. Social media platforms such as Facebook scoop up our posts and our user behavior data. Google scans our emails. Amazon tracks our shopping history.

Countless other companies harvest our data or purchase it from data aggregators. Our data can be used against us, and the current privacy laws do not do enough to protect against the aggregated data harms of today’s connected world. The United States doesn’t even have a federal privacy law.

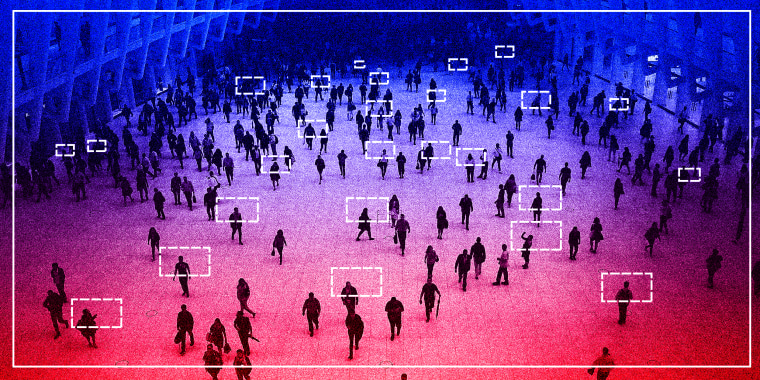

In the past 20 years, not only have we witnessed an explosion in government and corporate surveillance, but we have also seen an increase in public-private surveillance partnerships. Amazon now partners with over 2,000 law enforcement agencies in the nation, with agreements that involve the sharing of video and audio data from Ring cameras owned by private individuals.

Facial recognition company Clearview AI has been accused of selling surveillance technologies abroad, with little government oversight.

Facial recognition company Clearview AI has been accused of selling surveillance technologies abroad, with little government oversight. When we export such technology, we run the risk of supporting oppressive regimes that may then use it to stamp down political dissent, oppress minorities and commit human rights abuses. Clearview's CEO has acknowledged interest from other countries but says the company is "very much focused on the U.S. and Canada" and that it would not do business inside countries that are "very adverse to the U.S."

We need better and stronger laws to protect privacy and individual rights, especially during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Twenty years ago, we surrendered privacy rights for national security and safety. Today, we may be surrendering even more privacy rights for the cause of public health.

Safety and public health are important, and it is critical that the government protect both. However, just as 9/11 changed the way we thought about privacy and civil liberties, today, the pandemic is changing the way we evaluate the tradeoffs between protecting individual rights and protecting public health.

We mustn’t lose sight of the importance of privacy in safeguarding our freedom and autonomy. There is still time to fight for our rights against both government and corporate intrusion and to protect our privacy and other civil liberties before it’s too late.

We can’t go back to the days before the pandemic or before 9/11. However, we can create a better “new normal.” We can stop exporting surveillance technologies to countries where we know the tech will be used to commit atrocities. We can impose stricter standards on privacy and require protections of civil liberties for corporations and our government. We can pass a federal privacy law. We can work with like-minded nations to raise the bar for privacy and human rights worldwide, setting new norms and legal standards for the world — thereby helping not only our fellow Americans but the entire human race.

We can do this because, despite the rise in surveillance since 9/11 and the new corporate-driven data ecosystem, we still live in a free democracy. We have the right to speak freely and raise our voices for what we believe in, even if it involves curtailing the power of the government. We have a free market that allows us to vote with our wallets and a fair electoral process that allows us to choose the people who govern us.

Privacy and civil liberties are the bedrock of our democracy. We must do better not only for ourselves, but because the rest of the world is watching. If we can protect privacy, freedom and democracy in America, we help the cause of democracy and freedom worldwide, now and in the future. That future is worth fighting for, always.