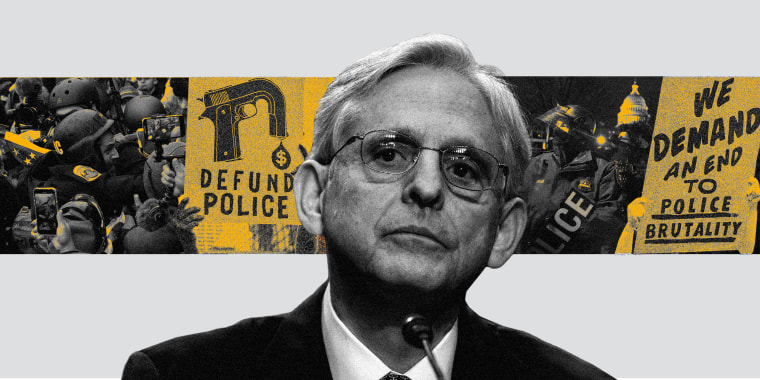

Judge Merrick Garland spent a good chunk of time at his confirmation hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday knocking away some of the GOP's most pressing culture war concerns, including the fight over whether to "defund the police."

But in making his case, the former prosecutor conflated the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol with the need to keep police departments well-funded around the country. And, well, that just doesn't add up.

If he is confirmed as attorney general, Garland's Justice Department will have to transform vague pledges to hold police accountable in the shadow of last year's Black Lives Matter protests into policy. But he has to do so while also holding off Republicans from using the "defund the police" slogan as a political bludgeon, which President Joe Biden thinks they did to "beat the living hell" out of Democrats in the election.

That dynamic is why Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., used his time questioning Garland to warn of a "mounting crime wave" and ask whether the nominee wants to "send exactly the wrong message to law enforcement" by supporting the idea of defunding the police.

"President Biden has said he does not support defunding the police, and neither do I," Garland responded. "We saw how difficult the lives of police officers were in the bodycam videos we saw when they were defending the Capitol. I do believe, and President Biden believes, in giving resources to police departments to help them reform and gain the trust in their communities."

Now, I get why that makes sense on a surface level: If you defund the police, how do you prevent violence from bad actors like we saw in Washington? Who could possibly watch the harrowing video of white supremacists, conspiracy theorists and other Trump supporters attacking Capitol Police officers and agree that they need fewer resources?

Any debate over reducing funding for local police in response to brutality against minority communities can't be applied to police actions to defend members of Congress from an armed mob.

But there's no real link between the two points. It's a complete red herring. Any debate over reducing funding for local police in response to brutality against minority communities can't be applied to police actions to defend members of Congress from an armed mob.

Though they disagree on most things, Garland's argument shared oddly similar underpinnings with one that professional contrarian Glenn Greenwald made on Twitter on Feb. 17. "I also find it odd, and more than a little disturbing how little interest there is in the question of whether the point-blank shooting by a police officer of unarmed Ashli Babbitt was justified," Greenwald said in a thread linking to his latest newsletter. "Especially after the police protests of last summer, the indifference is striking."

The perceived indifference Greenwald denounces boils down to very real differences between the two events — differences that Garland should take into account. The insurrection and the Capitol Police response are entirely separate from the actions that sparked the last round of Black Lives Matters protests. George Floyd's death on the streets of Minneapolis, Louisville, Kentucky, police shooting Breonna Taylor in her home, officers in Aurora, Colorado, killing Elijah McClain after stopping him as he walked home are all examples of the state's carrying out a lethal sentence in the absence of a crime or a clear and present danger. All show the impunity law enforcement acts with unless it is pressured to show accountability.

Compare those stories to that of Babbitt, who tragically believed she was acting in the right when she tried to storm the House chamber. Babbitt's death didn't provoke the same outcry as Taylor's or Floyd's because, absent her actions, the racial power imbalances in Minneapolis and Louisville wouldn't have involved her. There was little to no chance that she would have been stopped on the street for wearing a mask in the "wrong neighborhood," no chance that she would be held in a chokehold as she tried to yell that she couldn't breathe.

In the end, the question at the heart of the matter is whether the police forces in question are using their powers in defense or whether their actions are offensive, in multiple uses of the word. At the Capitol, the federally funded officers were defending members of Congress. As they were under assault, some Black officers reported being called the n-word and otherwise being subjected to racist abuse at the hands of the would-be putschists.

All too often, though, police officers around the country bend, skirt or outright defy the law as they harass, harangue and otherwise harm Black and brown people they should be defending.

An independent investigation released Monday showed that none of the officers who stopped McClain on the street "articulated a crime that they thought Mr. McClain had committed, was committing, or was about to commit." He was stopped, instead, because he was "acting 'suspicious,' was wearing a mask and waving his arms, and he was in an area with a 'high crime rate.'" None of the reasons given later were grounds for a lawful stop, nor for the frisk that was administered, nor for the many forms of pain that were administered to gain his compliance before ketamine was injected into his body and ultimately killed him.

These demands all share an interest in correcting the wildly unbalanced power dynamic between the armed officers of the state and the people they are supposed to serve.

Even last week, as Texas dealt with a winter storm that left millions of people unsafe and without power, police found time to arrest a young Black man for walking down the street during the snowstorm instead of taking him home. How is that in the interest of defending the community?

In practice, the calls to reduce police funding range from merely transferring funds for police departments to emergency medical services and social workers to abolishing municipal police units altogether. In principle, though, these demands all share an interest in correcting the wildly unbalanced power dynamic between the armed officers of the state and the people they are supposed to serve. None of that applies to an armed assault on democracy in favor of white supremacy — especially one that was reported to have included police officers in its ranks.

At his confirmation hearing, Garland promised that if he's confirmed, he'll work to address systemic racism in the criminal justice system. That will have to include ensuring that police departments act in the best interests of all members of their communities. Sometimes that will require Garland to buck his history of siding with law enforcement in criminal rulings.

The bulk of the work will fall mostly on the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division, which was, for the most part, ignored during the Trump administration. Biden's nominee to head this section, Kristen Clarke, is already having to fend off right-wing attacks on her past comments about race. She's going to need Garland's firm support to do her job — someone needs to defend her while she's defending Americans from their police.